An instrument, a ‘Japanese’, and the frailty of intercultural existence Hugh de Ferranti

I’m thinking about an object I’ve encountered while doing research on music and the Japanese in prewar Australia. It’s a musical instrument - and for once in my academic life, it’s not the biwa琵琶! Since 2018 the mandolin, an instrument I’d previously enjoyed hearing but hardly thought about, for me has come to be strongly associated with Joseph Clement Kisaburo Murakami, who died in Kawasaki last month, aged 94. It has a less explicit but visibly evident association, too, with others in the Japanese communities of the 1930s and 1940s. I will consider how the mandolin was experienced, most of all by that striking individual, the late Joe Murakami, as a tool for pleasure, leisure, interpersonal and potentially intercultural connections, but also how it may have come to symbolise the ultimate frailty of those connections in an era of racial prejudice, ethnic nationalism, war and postwar bitterness.

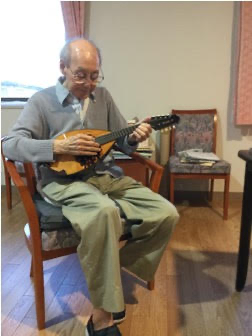

Photo taken by the author, November 2018

Joe was born in 1927 in Broome (in the northern coastal region of Western Australia) as the child of an Australian-born mother of Japanese heritage and a Japanese migrant father. He was a British Subject – a status roughly equivalent to what became Australian citizenship in 1948. (As a Nikkei Australian he received citizenship in 1950, although subsequently he unsuccessfully tried to obtain Japanese citizenship.) Nonetheless he was born with a Japanese name and face in an Australia where the public was already anxious about expanding Japanese imperial power. The government often shared that disquiet, so generally treated Australian-born and naturalised British Subjects of Japanese heritage as ‘Japanese’ rather than ‘Australians’, a category that at that time commonly implied those of Anglo-Celtic heritage, excluding even the indigenous people of the Australian continent. Such institutionalised racism mattered little to Joe during his childhood and early teen years in Australia’s tropical ‘polyethnic North’ (Ganter 2006), but when the War came in December 1941 it determined his fate; like all Japanese nationals and almost all Japanese-heritage people in Australia (‘Japanese’),i he was interned as an ‘unwanted alien’ (Nagata 1996).

Joe played the mandolin when he was young. He told me that in 2018, a few months after I’d been introduced to him by the historian Nagata Yuriko. I would sometimes go from Tokyo Tech to visit him at the nursing home in Kawasaki where he’d been living, at first to do more-or-less structured interviews, but before long simply to enjoy chatting. I felt that Joe had very few chances to speak English, his first language, much less talk to anyone who had a genuine understanding of life in Australia, where he’d lived until age 35, and had regularly visited to see relatives until the early 2000s. I sensed he enjoyed the opportunity to talk, so I went to see him whenever I could find time.

Joe said he’d not touched a mandolin since moving to Japan in 1964 to take up a job opportunity in the early years of ‘the Economic Miracle’, so I never got to hear him play. I will later ponder why it was that he left the instrument and music behind in Australia, but first I want to consider the mandolin itself, how it came to him, and by his own account what he did with it.

In most cultures instruments are experienced and ranked according to a hierarchy that reflects broader cultural practices and values. In ‘Western’ musical culture, which has provided the prevalent - but certainly not the sole - conceptual framework for musicking in much of the modern world, the mandolin has an ambiguous, unstable status. (That status seems unrelated to its ongoing core role in much southern Italian regional musicking.) A novelty instrument of ‘exotic’ Mediterranean origin for bourgeois amateurs in mid-C19th USA and Britain, by 1900 it was chiefly associated with vaudeville and music hall entertainment. Like guitar, it has been and still is played by millions of amateurs, but notwithstanding a Vivaldi concerto and a handful of other ‘classical’ mandolin compositions, it lacks the high art credentials and repertoire that accrued to the Spanish guitar from the mid-C19th. Today most think of mandolin as a folk instrument whose sound is important in traditional and ‘old-time’ genres such as early bluegrass, but otherwise a peripheral ‘thing’ despite its occasional forays into mainstream popular genres. The adoption of mandolin in non-Western music traditions, for example in north Indian Hindustani classical music, is hardly known of.

I encountered mandolins long before I met Joe Murakami. For a middle-class teenager in 1970s Sydney, the sound and occasional sight of mandolins was unavoidable, on LPs and in concerts by neo-traditional folk musicians, and British and home-grown folk-rock groups. I even enjoyed some mandolin ‘riffs’ devised by hard rock icons like Led Zeppelin’s bass player, such as the catchy one that tumbles along under Sandy Denny’s ethereal voice in a vocal duet on ‘the 4th album’. Decades later, I came to know that the instrument had been played in Japan since the mid-1890s, and that mandolin clubs have had a major presence in Japanese high school music culture. Then after I took up a job at Tokyo Tech I enjoyed talking about and hearing the instrument in the hands of my colleague (in Foreign Languages and now here in Future of Humanity Research Center) 木内久美子 !

It was Kumiko, in fact, who loaned me a precious bowl-back mandolin she’s had since her high school days, so that I could take it along to show to Joe at his room in the nursing home. Joe knew that I was researching music and the Japanese communities in interwar Australia, so he had patiently told me some of his musical memories, which included involvement with mandolin from around the age of nine (in 1936) right through his teen years ending in 1946 - and perhaps even after, in the immediate postwar years and the 1950s, when anyone with a Japanese name endured much bitterness and hardship in Australian society. Joe first held a mandolin at St. Mary’s Catholic convent school in Darwin after his family had moved there from the isolated Western Australian town of Broome, a place that had seen fame as a site of production of superb quality pearl shell in demand throughout the world. Joe’s mother was Australian-born and raised as a staunch Catholic, so after the move to Darwin in 1935 her younger children were sent to the local convent school. At that time the nuns at St. Mary’s gave priority to musical education, regardless of the diverse and mixed ethnicities of children in their care; consequently Joe soon was loaned a bowl-back mandolin by the school, while one of his sisters received tuition in piano.

In conversation with Joe I remember asking whether he’d taught himself to play tunes from 1930s 流行歌 he’d heard on SP盤 (78rpm) records given to his parents by pearl shell divers going home at the end of their contracts in Broome or Darwin. Yet he said he’d never once played a Japanese melody on the mandolin! My assumption that he must have tried to play Japanese song tunes stemmed from a kind of ethnic essentialism, whereby ‘Japanese (popular) music’ seemed an inevitable choice for an ethnically Japanese boy who grew up in a small Japanese migrant community. But no, Joe’s first language – and likewise his Australian-born mother’s - was English, and many of his interests were no different to those of ‘white’ boys who grew up in the tropical Monsoon North of Australia: He wanted to play American hit tunes and songs, some of which were first heard in Hollywood movies shown at the picture theatres that were such important sites of leisure and mediated ‘global connection’ for young people in the remote towns of the North.

Regardless of how well Joe could play movie tunes then familiar to most young Australians, as a 14 year-old regarded by authorities as ‘a Jap’ he was forcibly removed from his Darwin home along with all his family on the day after the Pearl Harbour attack. No one was allowed to take anything more than clothing and bare necessities - musical instruments were out of the question. After a sea journey in conditions of privation around the continent to Sydney, then another trip of several hundred kilometres inland by train, Joe’s family and hundreds of others, Japanese and ‘Japanese’ alike, arrived at Tatura, the civilian wartime internment camp in the Goulburn region of central Victoria. Some fell ill and died prematurely there in the camp, including Joe’s father Yasukichi, a renowned photographer, inventor and a leader of the Japanese community in Darwin, while most were eventually deported to Japan – a land that quite a few of them had never set foot in. Those allowed to remain in Australia didn’t leave the camp until 1946, well after the War had ended. Joe spent almost all his teen years as an internee, with lifelong consequences for his education and social development (Nagata 2017). Yet he played music during some of those six long years. Being allowed to order certain items through a mail order catalogue, he purchased a flatback mandolin. When I asked about what music he’d played under those extraordinary circumstances, he spoke mostly about a duo he’d formed with a guitarist, an internee from the Solomon Islands who’d been regarded as a ‘Jap sympathiser’ and thereby a wartime risk to his society. The middle-aged man from an isolated set of islands to the east of New Guinea, a doctor by profession, and the teenage ‘Japanese’ Australian strummed together for their own pleasure and that of anyone willing to listen – fellow internees or even guards. When holding my colleague’s precious instrument, Joe was not willing to try to play, for the reason that he’d not touched a mandolin during the 55 years he’d been living in Japan. However, he hummed for me phrases from the tune of a duet they’d often played in the Tatura camp. Lo and behold it was a late 1930s Italian melody, “Reginella Campagnola” (still well-loved in Italy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WCbQ36QZ_mU), which had found its way into mainstream American music as “The Woodpecker Song”, a 1940 swing orchestra hit recorded by Glen Miller with the Andrews Sisters, and in turn became a Hollywood movie song in the same year (in Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride.)

Here is a professional mandolin and guitar duo’s rendition in 2009:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YuESgbKUXdo

Soon after that talk with Joe, I found two remarkable images. One was a photo of another young Japanese who’d enjoyed playing mandolin around 1940: Standing in front of one of the Japanese marine workers’ dormitories on Thursday Island, a 20-something-year old diver held the instrument (bowl-backed) with one hand and an infant child in the crook of his other arm. Clearly both child (presumably his own) and instrument were dear to the heart of that young man. Marine contract workers led very tough lives for most of the year, but during the ‘lay up’ months when diving for shells was not possible, they had a lot of leisure time, and just as in the Tatura camp, the mandolin and other instruments resounded to pass some of those long hours. Being a highly portable instrument, moreover, mandolins most likely were taken out on the pearling luggers (as was shakuhachi; Konishi and Hayward 2001) and strummed on deck after sunset.

There are no images or accounts of that, but this shows the mandolin in 1920s outdoor (Greek migrant) leisure:

https://opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/physical_object/Picnic_in_Red_Cliffs_Victoria_1927/16600328

The other image was a handful of frames in a 1946 colour film (Barmera Visitor Information Centre and Berri-Barmera Council ) showing a homemade mandolin in the hands of a Japanese-heritage carpenter and wood sculptor who was then still stuck at the Loveday internment camp. Presumably he, too, played mandolin as he’d gone to all the trouble of constructing one with makeshift materials.

Joe grew up with much the same interests as young Anglo-Australians like those who eventually detained, transported then guarded him and his family in internment for six years. The mandolin came to popularity in 1920s-30s Japan by entirely different routes to the ones that led it to Joe via the music program at the convent school. Yet it was important to the wellbeing of Joe, a schoolboy in Darwin, and for some young indentured divers on Thursday island, and a number of ‘Japanese’ interned in the wartime camps, along with Solomon Islanders and others from Melanesia and Micronesia - just as it was for thousands of European migrants and Anglo-Australians at the time.

For me, Joe’s enjoyment of the mandolin as a teenager, in an era of racial distrust and in turn outright dehumanisation during wartime, can be symbolic of interethnic exploration and connection, and the never-ending daily work of intercultural existence. Through the research I’ve done these last few years, the ‘music thing’ (instrument) called mandolin has come to signify something else - potential for meaningful intercultural connection in the histories of Joe’s (and my) two countries and peoples. Yet the truth is that at 34 Joe gave up playing mandolin along with one of those countries – he never touched the instrument again (until the day I borrowed my colleague’s and brought it to his room), just as he never resided in Australia again. Why? Joe didn’t say, so I will never know, but from what he did say, I infer as follows: It wasn’t just a matter of how hard it was for a man in his mid-thirties to start a new life in a new society, in a setting where he could speak the language moderately well but had to study hard to become literate in it. As well as finding the huge amounts of time and energy required to do that, I think Joe probably also had to make a break within himself, a clean break with ‘things’ he associated with the greater hardships of the years he’d spent in internment in his own country, then in postwar Australian society – his own society, but one suffused with vehement anti-Japanese sentiment. As I said, Joe claimed he’d never played a Japanese melody on mandolin, so it seems both the instrument and the music he’d played on it were among those things that were utterly of his former life, but not of the new life he built in 1960s Tokyo.

Instruments and their repertories cut both ways: under particular conditions they bring people of disparate ethnic origins and lifeways together, but under others – most especially war and its long aftermath - they remind people of how they were driven apart. Musical ‘things’ such as instruments, but also songs or tunes, can be so redolent of places and deeply felt experiences for some individuals that they are best left untouched and unheard.

I can’t but wonder what (music) things beloved of Russians and Ukrainians alike are right now allaying – or being forgotten in - the furies of war.